White Swans and the Moron Risk Premium

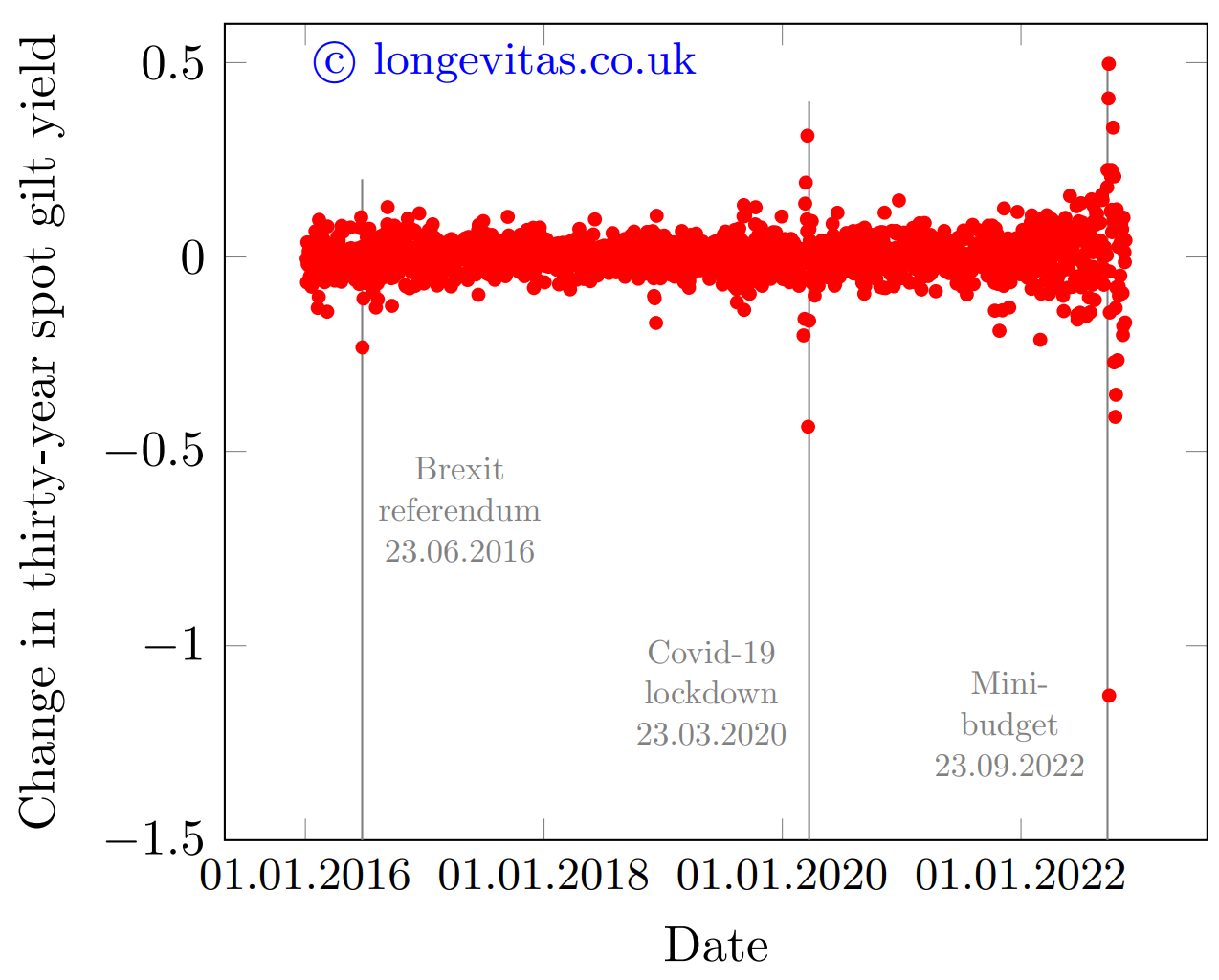

Interest rates and gilt yields are critical drivers of pension-scheme reserving and bulk-annuity pricing. However, many UK pension schemes self-insure when it comes to economic risks, with Liability Driven Investment (LDI) a common approach. This makes the turmoil in the UK Gilts market in Autumn 2022 of particular interest. Daily movements of 10-20 standard deviations arose as the budget of the 23rd September shook investor confidence in the UK, crashing the pound and pushing up Gilt yields. This was amplified by an adverse feedback loop with margin calls arising from LDI investment strategies forcing pension schemes to dump Gilts and other assets on the market. The exceptional nature of this can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. One-day changes in spot yields on 30-year UK nominal gilts. Source: own calculations using Bank of England yields[1].

It is understandable that many models of Gilt yield movements would not forecast such extreme movements, but this does not make the turmoil a “black swan” event that could not have been foreseen. On the contrary, the vulnerabilities that created the crisis were well known.

The loss of foreign investor confidence in the UK is a threat the Bank of England (BoE) has called out for many years, noting the UK’s reliance on overseas investors to fund its large current account deficit. Indeed, as the risk of a hard Brexit loomed in 2019, the BoE incorporated just such a loss of confidence into the Annual Cyclical Scenario (ACS) it uses to stress test banks. The effects of this included the pound falling below parity with the US dollar and Gilt yields rising to nearly 7% p.a., far beyond the movements seen in autumn 2022[2].

Similarly, the vulnerability of pension schemes to margin calls while invested in illiquid assets was highlighted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its 2019 Global Financial Stability Report[3]. Furthermore, redemptions by pension schemes to meet such margin calls nearly triggered a crisis in money-market funds during March 2020, which should have given pause for thought[4]. Some LDI strategies involve investment funds borrowing money short-term to gear-up interest rate exposure. However, a cursory analysis of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 would have shown that markets can seize up and it is not always be possible to roll-over such loans when one might need them most.

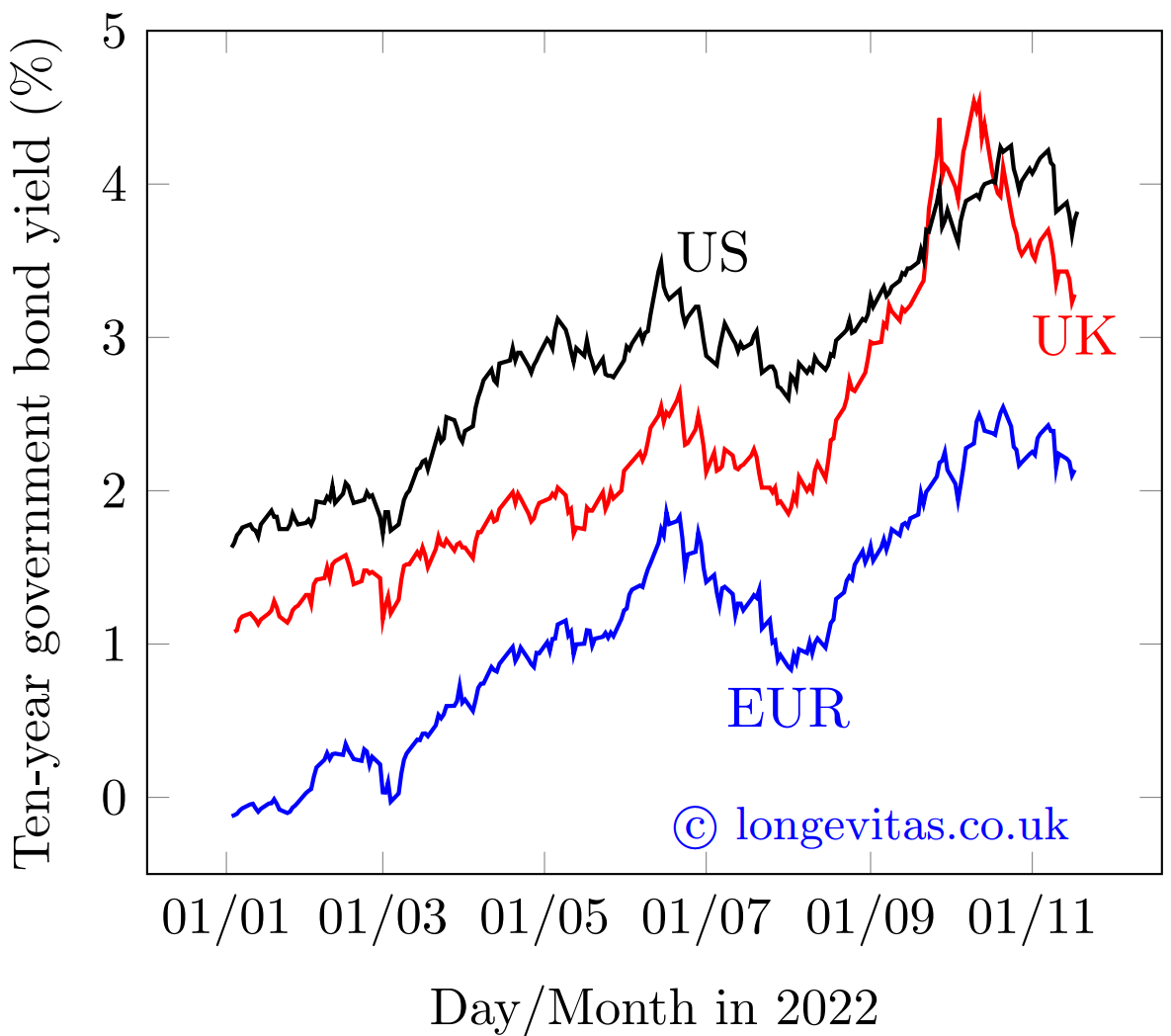

Even if one was unaware of these vulnerabilities, a comparison of UK Gilt yields with other government bonds indicated trouble brewing in the run-up to the budget, as Figure 2 shows:

Figure 2. Ten-year sovereign bond yields. Source: Bank of England, US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank[5].

Figure 2 shows UK Gilts yields broadly moving in tandem with US T- bonds and other highly rated sovereign debt. However, from the start of August we start to see a marked divergence, with UK Gilt yields rising relative to other sovereign bonds. I have little doubt that this divergence was due to investors being spooked by the prospect of Prime Minister Truss’s unfunded tax cuts and spending on energy support. Even Truss's own economic adviser warned that her tax cuts would increase inflation and push interest rates up to 7% p.a.[6].

Undeterred, Truss and her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, pushed on with their plans, resulting in market turmoil as UK Gilt yields rose above those of US T-bonds. This reversal of the usual relationship was termed the “moron risk premium” by Dario Perkins of the investment research firm TS Lombard. Woody Allen once joked that the Russian revolution arose when people realised the Tsar and Czar were the same person. Similarly, investors realised that the highly-rated UK issuing gilt-edged securities was the same country with a massive current-account deficit and anaemic economic growth. It has taken a change in Prime Minister and Chancellor, coupled with a return to austerity, to reassure markets.

To conclude, far from being a “black swan”, the turmoil in Gilt markets was a “white swan” which could and should have been foreseen by prudent politicians taking expert advice. The UK's reliance on investor confidence to fund its current-account deficit was well known, and the bond markets gave clear signals in the run-up to the budget. Similarly, the potential impact of a spike in Gilt yields on LDI strategies is something pension schemes should have been aware of.

Going forward, one hopes that UK politicians have learned the lesson that they ignore bond markets at their peril. Similarly, pension schemes should learn lessons in managing liquidity risks associated with LDI, looking beyond models to robust stress testing along the lines of the BoE’s ACS. Better emerging risk identification is required, incorporating information from Financial Stability Reports and other sources.

References:

[1] Peak daily rise and fall in 30-year Gilts was +50bps and -113bps respectively, compared to a standard deviation in daily movements of 5bps based on data from 1/1/2016 to 21/9/2022 sourced from the Bank of England – see Yield curves | Bank of England.

[2] See Key elements of the 2019 stress test | Bank of England; note however that the scenario movements take place over a much longer timescale than the days and weeks after 23/9/2022.

[3] See chapter 3 of “Global Financial Stability Report – Lower for Longer”, IMF October 2019, available at Global Financial Stability Report, October 2019: Lower for Longer (imf.org)

[4] See the section “Building the resilience of market-based finance”, p65-87 of the BoE’s August 2020 Financial Stability Report, available at: Monetary Policy Report and Financial Stability Report - August 2020 | Bank of England

[5] UK Gilt yield data sourced from BoE as in [1]; US Treasury Bond data sourced from the US Federal Reserve – see Federal Reserve Board - Nominal Yield Curve; EU AAA-rated sovereign bond data sourced from the European Central Bank – see Euro area yield curves (europa.eu)

[6] “Liz Truss’s tax cuts could cause 7% interest rates, warns her own economics guru”, Richard Vaughan, MSN, 22nd July available at: Liz Truss’s tax cuts could cause 7% interest rates, warns her own economics guru (msn.com)

Add new comment